Checkpoint 4.3.2.

What is the correct order of Git commands to initialize a new repository, add a README, and make the first commit?

$ cd /home/user/my_project

$ cd /Users/user/my_project

$ cd C:/Users/user/my_project

$ git init

.git that contains all of your necessary repository files — a Git repository skeleton. At this point, nothing in your project is tracked yet.git add commands that specify the files you want to track, followed by a git commit:$ git add *.c $ git add LICENSE $ git commit -m 'Initial project version'

git clone. If you’re familiar with other VCSs such as Subversion, you’ll notice that the command is "clone" and not "checkout". This is an important distinction — instead of getting just a working copy, Git receives a full copy of nearly all data that the server has. Every version of every file for the history of the project is pulled down by default when you run git clone.git clone <url>. For example, if you want to clone the Git linkable library called libgit2, you can do so like this:$ git clone https://github.com/libgit2/libgit2

libgit2, initializes a .git directory inside it, pulls down all the data for that repository, and checks out a working copy of the latest version. If you go into the new libgit2 directory that was just created, you’ll see the project files in there, ready to be worked on or used.libgit2, you can specify the new directory name as an additional argument:$ git clone https://github.com/libgit2/libgit2 mylibgit

mylibgit.https:// protocol, but you may also see git:// or user@server:path/to/repo.git, which uses the SSH transfer protocol.

git status command. If you run this command directly after a clone, you should see something like this:$ git status On branch main Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'. nothing to commit, working tree clean

main, which is the current default. It could also be main, which was the default until October 1, 2020. Don’t worry about it here. The next section on Git Branching will go over branches and references in detail.README file. If the file didn’t exist before, and you run git status, you see your untracked file like so:$ echo 'My Project' > README

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

README

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

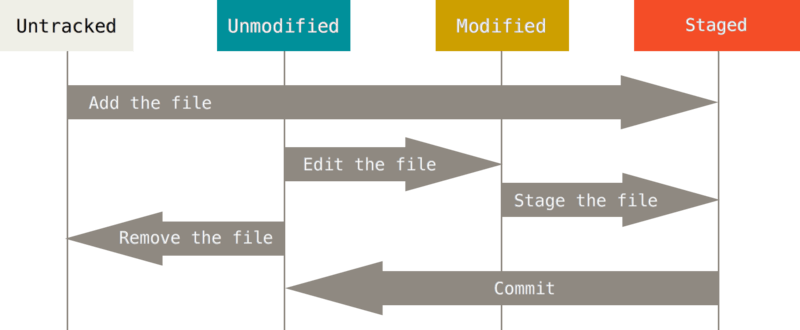

README file is untracked, because it’s under the “Untracked files” heading in your status output. Untracked basically means that Git sees a file you didn’t have in the previous snapshot (commit), and which hasn’t yet been staged; Git won’t start including it in your commit snapshots until you explicitly tell it to do so. It does this so you don’t accidentally begin including generated binary files or other files that you did not mean to include. You do want to start including README, so let’s start tracking the file.git add. To begin tracking the README file, you can run this:$ git add README

README file is now tracked and staged to be committed:$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README

git add is what will be in the subsequent historical snapshot. You may recall that when you ran git init earlier, you then ran git add <files> — that was to begin tracking files in your directory. The git add command takes a path name for either a file or a directory; if it’s a directory, the command adds all the files in that directory recursively.CONTRIBUTING.md and then run your git status command again, you get something that looks like this:$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

CONTRIBUTING.md file appears under a section named “Changes not staged for commit” — which means that a file that is tracked has been modified in the working directory but not yet staged. To stage it, you run the git add command. git add is a multipurpose command — you use it to begin tracking new files, to stage files, and to do other things like marking merge-conflicted files as resolved. It may be helpful to think of it more as “add precisely this content to the next commit” rather than “add this file to the project”. Let’s run git add now to stage the CONTRIBUTING.md file, and then run git status again:$ git add CONTRIBUTING.md

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README

modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

CONTRIBUTING.md before you commit it. You open it again and make that change, and you’re ready to commit. However, let’s run git status one more time:$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README

modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

CONTRIBUTING.md is listed as both staged and unstaged. How is that possible? It turns out that Git stages a file exactly as it is when you run the git add command. If you commit now, the version of CONTRIBUTING.md as it was when you last ran the git add command is how it will go into the commit, not the version of the file as it looks in your working directory when you run git commit. If you modify a file after you run git add, you have to run git add again to stage the latest version of the file:$ git add CONTRIBUTING.md

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README

modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

git status output is pretty comprehensive, it’s also quite wordy. Git also has a short status flag so you can see your changes in a more compact way. If you run git status -s or git status --short you get a far more simplified output from the command:$ git status -s M README MM Rakefile A lib/git.rb M lib/simplegit.rb ?? LICENSE.txt

?? next to them, new files that have been added to the staging area have an A, modified files have an M and so on. There are two columns to the output — the left-hand column indicates the status of the staging area and the right-hand column indicates the status of the working tree. So for example in that output, the README file is modified in the working directory but not yet staged, while the lib/simplegit.rb file is modified and staged. The Rakefile was modified, staged and then modified again, so there are changes to it that are both staged and unstaged..gitignore. Here is an example .gitignore file:$ cat .gitignore *.[oa] *~

~), which is used by some text editors to mark temporary files. You may also include a log, tmp, or pid directory; automatically generated documentation; and so on. Setting up a .gitignore file for your new repository before you get going is generally a good idea so you don’t accidentally commit files that you really don’t want in your Git repository. .gitignore file are as follows:# are ignored. /) to avoid recursivity. /) to specify a directory. !). *) matches zero or more characters; [abc] matches any character inside the brackets (in this case a, b, or c); a question mark (?) matches a single character; and brackets enclosing characters separated by a hyphen ([0-9]) matches any character between them (in this case 0 through 9). You can also use two asterisks to match nested directories; a/**/z would match a/z, a/b/z, a/b/c/z, and so on. .gitignore file:# ignore all .a files *.a # but do track lib.a, even though you're ignoring .a files above !lib.a # only ignore the TODO file in the current directory, not subdir/TODO /TODO # ignore all files in any directory named build build/ # ignore doc/notes.txt, but not doc/server/arch.txt doc/*.txt # ignore all .pdf files in the doc/ directory and any of its subdirectories doc/**/*.pdf

.gitignore file examples for dozens of projects and languages at https://github.com/github/gitignoregithub.com/github/gitignore.gitignore file in its root directory, which applies recursively to the entire repository. However, it is also possible to have additional .gitignore files in subdirectories. The rules in these nested .gitignore files apply only to the files under the directory where they are located. The Linux kernel source repository has 206 .gitignore files..gitignore files; see man gitignore for the details.git status command is too vague for you — you want to know exactly what you changed, not just which files were changed — you can use the git diff command. We’ll cover git diff in more detail later, but you’ll probably use it most often to answer these two questions: What have you changed but not yet staged? And what have you staged that you are about to commit? Although git status answers those questions very generally by listing the file names, git diff shows you the exact lines added and removed — the patch, as it were.README file again and then edit the CONTRIBUTING.md file without staging it. If you run your git status command, you once again see something like this:$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: README

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

git diff with no other arguments:$ git diff diff --git a/CONTRIBUTING.md b/CONTRIBUTING.md index 8ebb991..643e24f 100644 --- a/CONTRIBUTING.md +++ b/CONTRIBUTING.md @@ -65,7 +65,8 @@ branch directly, things can get messy. Please include a nice description of your changes when you submit your PR; if we have to read the whole diff to figure out why you're contributing in the first place, you're less likely to get feedback and have your change -merged in. +merged in. Also, split your changes into comprehensive chunks if your patch is +longer than a dozen lines. If you are starting to work on a particular area, feel free to submit a PR that highlights your work in progress (and note in the PR title that it's

git diff --staged. This command compares your staged changes to your last commit:$ git diff --staged diff --git a/README b/README new file mode 100644 index 0000000..03902a1 --- /dev/null +++ b/README @@ -0,0 +1 @@ +My Project

git diff by itself doesn’t show all changes made since your last commit — only changes that are still unstaged. If you’ve staged all of your changes, git diff will give you no output.CONTRIBUTING.md file and then edit it, you can use git diff to see the changes in the file that are staged and the changes that are unstaged. If our environment looks like this:$ git add CONTRIBUTING.md

$ echo '# test line' >> CONTRIBUTING.md

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

git diff to see what is still unstaged:$ git diff diff --git a/CONTRIBUTING.md b/CONTRIBUTING.md index 643e24f..87f08c8 100644 --- a/CONTRIBUTING.md +++ b/CONTRIBUTING.md @@ -119,3 +119,4 @@ at the ## Starter Projects See our [projects list](https://github.com/libgit2/libgit2/blob/development/PROJECTS.md). +# test line

git diff --cached to see what you’ve staged so far (--staged and --cached are synonyms):$ git diff --cached diff --git a/CONTRIBUTING.md b/CONTRIBUTING.md index 8ebb991..643e24f 100644 --- a/CONTRIBUTING.md +++ b/CONTRIBUTING.md @@ -65,7 +65,8 @@ branch directly, things can get messy. Please include a nice description of your changes when you submit your PR; if we have to read the whole diff to figure out why you're contributing in the first place, you're less likely to get feedback and have your change -merged in. +merged in. Also, split your changes into comprehensive chunks if your patch is +longer than a dozen lines. If you are starting to work on a particular area, feel free to submit a PR that highlights your work in progress (and note in the PR title that it is so.

git add on since you edited them — won’t go into this commit. They will stay as modified files on your disk. In this case, let’s say that the last time you ran git status, you saw that everything was staged, so you’re ready to commit your changes. The simplest way to commit is to type git commit:$ git commit

EDITOR environment variable, although you can configure it with whatever you want using the git config - -global core.editor command as you saw in the previous section.# Please enter the commit message for your changes. Lines starting # with '#' will be ignored, and an empty message aborts the commit. # On branch main # Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'. # # Changes to be committed: # new file: README # modified: CONTRIBUTING.md # ~ ~ ~ ".git/COMMIT_EDITMSG" 9L, 283C

git status command commented out and one empty line on top. You can remove these comments and type your commit message, or you can leave them there to help you remember what you’re committing.-v option to git commit. Doing so also puts the diff of your change in the editor so you can see exactly what changes you’re committing.commit command by specifying it after a -m flag, like this:$ git commit -m "Story 182: fix benchmarks for speed" [main 463dc4f] Story 182: fix benchmarks for speed 2 files changed, 2 insertions(+) create mode 100644 README

main), what SHA-1 checksum the commit has (463dc4f), how many files were changed, and statistics about lines added and removed in the commit.-a option to the git commit command makes Git automatically stage every file that is already tracked before doing the commit, letting you skip the git add part:$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

$ git commit -a -m 'Add new benchmarks'

[main 83e38c7] Add new benchmarks

1 file changed, 5 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

git add on the CONTRIBUTING.md file in this case before you commit. That’s because the -a flag includes all changed files. This is convenient, but be careful; sometimes this flag will cause you to include unwanted changes.git rm command does that, and also removes the file from your working directory so you don’t see it as an untracked file the next time around.git status output:$ rm PROJECTS.md

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add/rm <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

deleted: PROJECTS.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

git rm, it stages the file’s removal:$ git rm PROJECTS.md

rm 'PROJECTS.md'

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

deleted: PROJECTS.md

-f option. This is a safety feature to prevent accidental removal of data that hasn’t yet been recorded in a snapshot and that can’t be recovered from Git..gitignore file and accidentally staged it, like a large log file or a bunch of .a compiled files. To do this, use the --cached option:$ git rm --cached README

git rm command. That means you can do things such as:$ git rm log/\*.log

\) in front of the *. This is necessary because Git does its own filename expansion in addition to your shell’s filename expansion. This command removes all files that have the .log extension in the log/ directory. Or, you can do something like this:$ git rm \*~

~. mv command. If you want to rename a file in Git, you can run something like:$ git mv file_from file_to

$ git mv README.md README

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

renamed: README.md -> README

$ mv README.md README $ git rm README.md $ git add README

mv command. The only real difference is that git mv is one command instead of three — it’s a convenience function. More importantly, you can use any tool you like to rename a file, and address the add/rm later, before you commit.git log command.$ git clone https://github.com/schacon/simplegit-progit

git log in this project, you should get output that looks something like this:$ git log

commit ca82a6dff817ec66f44342007202690a93763949

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gee-mail.com>

Date: Mon Mar 17 21:52:11 2008 -0700

Change version number

commit 085bb3bcb608e1e8451d4b2432f8ecbe6306e7e7

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gee-mail.com>

Date: Sat Mar 15 16:40:33 2008 -0700

Remove unnecessary test

commit a11bef06a3f659402fe7563abf99ad00de2209e6

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gee-mail.com>

Date: Sat Mar 15 10:31:28 2008 -0700

Initial commit

git log lists the commits made in that repository in reverse chronological order; that is, the most recent commits show up first. As you can see, this command lists each commit with its SHA-1 checksum, the author’s name and email, the date written, and the commit message.git log command are available to show you exactly what you’re looking for. If interested, see git-log - Show commit logswww.git-scm.com/docs/git-log-p or --patch, which shows the difference (the patch output) introduced in each commit. You can also limit the number of log entries displayed, such as using -2 to show only the last two entries.$ git log -p -2

commit ca82a6dff817ec66f44342007202690a93763949

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gee-mail.com>

Date: Mon Mar 17 21:52:11 2008 -0700

Change version number

diff --git a/Rakefile b/Rakefile

index a874b73..8f94139 100644

--- a/Rakefile

+++ b/Rakefile

@@ -5,7 +5,7 @@ require 'rake/gempackagetask'

spec = Gem::Specification.new do |s|

s.platform = Gem::Platform::RUBY

s.name = "simplegit"

- s.version = "0.1.0"

+ s.version = "0.1.1"

s.author = "Scott Chacon"

s.email = "schacon@gee-mail.com"

s.summary = "A simple gem for using Git in Ruby code."

commit 085bb3bcb608e1e8451d4b2432f8ecbe6306e7e7

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gee-mail.com>

Date: Sat Mar 15 16:40:33 2008 -0700

Remove unnecessary test

diff --git a/lib/simplegit.rb b/lib/simplegit.rb

index a0a60ae..47c6340 100644

--- a/lib/simplegit.rb

+++ b/lib/simplegit.rb

@@ -18,8 +18,3 @@ class SimpleGit

end

end

-

-if $0 == __FILE__

- git = SimpleGit.new

- puts git.show

-end

git remote command. It lists the shortnames of each remote handle you’ve specified. If you’ve cloned your repository, you should at least see origin — that is the default name Git gives to the server you cloned from:$ git clone https://github.com/schacon/ticgit Cloning into 'ticgit'... remote: Reusing existing pack: 1857, done. remote: Total 1857 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0) Receiving objects: 100% (1857/1857), 374.35 KiB | 268.00 KiB/s, done. Resolving deltas: 100% (772/772), done. Checking connectivity... done. $ cd ticgit $ git remote origin

-v, which shows you the URLs that Git has stored for the shortname to be used when reading and writing to that remote:$ git remote -v origin https://github.com/schacon/ticgit (fetch) origin https://github.com/schacon/ticgit (push)

$ cd grit $ git remote -v bakkdoor https://github.com/bakkdoor/grit (fetch) bakkdoor https://github.com/bakkdoor/grit (push) cho45 https://github.com/cho45/grit (fetch) cho45 https://github.com/cho45/grit (push) defunkt https://github.com/defunkt/grit (fetch) defunkt https://github.com/defunkt/grit (push) koke git://github.com/koke/grit.git (fetch) koke git://github.com/koke/grit.git (push) origin git@github.com:mojombo/grit.git (fetch) origin git@github.com:mojombo/grit.git (push)

git clone command implicitly adds the origin remote for you. Here’s how to add a new remote explicitly. To add a new remote Git repository as a shortname you can reference easily, run git remote add <shortname> <url>:$ git remote origin $ git remote add pb https://github.com/paulboone/ticgit $ git remote -v origin https://github.com/schacon/ticgit (fetch) origin https://github.com/schacon/ticgit (push) pb https://github.com/paulboone/ticgit (fetch) pb https://github.com/paulboone/ticgit (push)

pb on the command line in lieu of the whole URL. For example, if you want to fetch all the information that Paul has but that you don’t yet have in your repository, you can run git fetch pb:$ git fetch pb remote: Counting objects: 43, done. remote: Compressing objects: 100% (36/36), done. remote: Total 43 (delta 10), reused 31 (delta 5) Unpacking objects: 100% (43/43), done. From https://github.com/paulboone/ticgit * [new branch] main -> pb/main * [new branch] ticgit -> pb/ticgit

main branch is now accessible locally as pb/main — you can merge it into one of your branches, or you can check out a local branch at that point if you want to inspect it. We’ll go over what branches are and how to use them in much more detail in the next subsection on Git Branching.$ git fetch <remote>

git fetch origin fetches any new work that has been pushed to that server since you cloned (or last fetched from) it. It’s important to note that the git fetch command only downloads the data to your local repository — it doesn’t automatically merge it with any of your work or modify what you’re currently working on. You have to merge it manually into your work when you’re ready.git pull command to automatically fetch and then merge that remote branch into your current branch. This may be an easier or more comfortable workflow for you; and by default, the git clone command automatically sets up your local main branch to track the remote main branch (or whatever the default branch is called) on the server you cloned from. Running git pull generally fetches data from the server you originally cloned from and automatically tries to merge it into the code you’re currently working on.git pull will give a warning if the pull.rebase variable is not set. Git will keep warning you until you set the variable.git config --global pull.rebase "false"

git config --global pull.rebase "true"

git push <remote> <branch>. If you want to push your main branch to your origin server (again, cloning generally sets up both of those names for you automatically), then you can run this to push any commits you’ve done back up to the server:$ git push origin main