12.5. Returning a value from a function¶

Not only can you pass a parameter value into a function, a function can also produce a value. You have already

seen this in some previous functions that you have used. For example, len takes a list or string as a parameter

value and returns a number, the length of that list or string. range takes an integer as a parameter value and

returns a list containing all the numbers from 0 up to that parameter value.

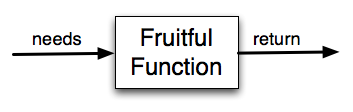

Functions that return values are sometimes called fruitful functions. In many other languages, a function that doesn’t return a value is called a procedure, but we will stick here with the Python way of also calling it a function, or if we want to stress it, a non-fruitful function.

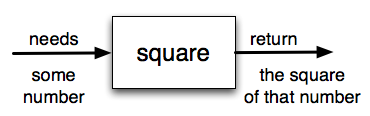

How do we write our own fruitful function? Let’s start by creating a very simple mathematical function that we will

call square. The square function will take one number as a parameter and return the result of squaring that

number. Here is the black-box diagram with the Python code following.

The return statement is followed by an expression which is evaluated. Its result is returned to the caller as the

“fruit” of calling this function. Because the return statement can contain any Python expression we could have

avoided creating the temporary variable y and simply used return x*x. Try modifying the square function

above to see that this works just the same. On the other hand, using temporary variables like y in the program

above makes debugging easier. These temporary variables are referred to as local variables.

Notice something important here. The name of the variable we pass as an argument — toSquare — has nothing to

do with the name of the formal parameter — x. It is as if x = toSquare is executed when square is

called. It doesn’t matter what the value was named in the caller (the place where the function was invoked). Inside

square, it’s name is x. You can see this very clearly in codelens, where the global variables and the local

variables for the square function are in separate boxes.

Activity: CodeLens 12.5.3 (clens11_4_1)

There is one more aspect of function return values that should be noted. All Python functions return the special value

None unless there is an explicit return statement with a value other than None. Consider the following common

mistake made by beginning Python programmers. As you step through this example, pay very close attention to the return

value in the local variables listing. Then look at what is printed when the function is over.

Activity: CodeLens 12.5.4 (clens11_4_2)

The problem with this function is that even though it prints the value of the squared input, that value will not be

returned to the place where the call was done. Instead, the value None will be returned. Since line 6 uses the

return value as the right hand side of an assignment statement, squareResult will have None as its value and

the result printed in line 7 is incorrect. Typically, functions will return values that can be printed or processed in

some other way by the caller.

A return statement, once executed, immediately terminates execution of a function, even if it is not the last statement in the function. In the following code, when line 3 executes, the value 5 is returned and assigned to the variable x, then printed. Lines 4 and 5 never execute. Run the following code and try making some modifications of it to make sure you understand why “there” and 10 never print out.

The fact that a return statement immediately ends execution of the code block inside a function is important to understand for writing complex programs, and it can also be very useful. The following example is a situation where you can use this to your advantage – and understanding this will help you understand other people’s code better, and be able to walk through code more confidently.

Consider a situation where you want to write a function to find out, from a class attendance list, whether anyone’s

first name is longer than five letters, called longer_than_five. If there is anyone in class whose first name is

longer than 5 letters, the function should return True. Otherwise, it should return False.

In this case, you’ll be using conditional statements in the code that exists in the function body, the code block

indented underneath the function definition statement (just like the code that starts with the line print("here")

in the example above – that’s the body of the function weird, above).

Bonus challenge for studying: After you look at the explanation below, stop looking at the code – just the description of the function above it, and try to write the code yourself! Then test it on different lists and make sure that it works. But read the explanation first, so you can be sure you have a solid grasp on these function mechanics.

First, an English plan for this new function to define called longer_than_five:

You’ll want to pass in a list of strings (representing people’s first names) to the function.

You’ll want to iterate over all the items in the list, each of the strings.

As soon as you get to one name that is longer than five letters, you know the function should return

True– yes, there is at least one name longer than five letters!And if you go through the whole list and there was no name longer than five letters, then the function should return

False.

Now, the code:

So far, we have just seen return values being assigned to variables. For example, we had the line

squareResult = square(toSquare). As with all assignment statements, the right hand side is executed first. It

invokes the square function, passing in a parameter value 10 (the current value of toSquare). That returns a

value 100, which completes the evaluation of the right-hand side of the assignment. 100 is then assigned to the

variable squareResult. In this case, the function invocation was the entire expression that was evaluated.

Function invocations, however, can also be used as part of more complicated expressions. For example,

squareResult = 2 * square(toSquare). In this case, the value 100 is returned and is then multiplied by 2 to

produce the value 200. When python evaluates an expression like x * 3, it substitutes the current value of x into

the expression and then does the multiplication. When python evaluates an expression like 2 * square(toSquare), it

substitutes the return value 100 for entire function invocation and then does the multiplication.

To reiterate, when executing a line of code squareResult = 2 * square(toSquare), the python

interpreter does these steps:

It’s an assignment statement, so evaluate the right-hand side expression

2 * square(toSquare).Look up the values of the variables square and toSquare: square is a function object and toSquare is 10

Pass 10 as a parameter value to the function, get back the return value 100

Substitute 100 for square(toSquare), so that the expression now reads

2 * 100Assign 200 to variable

squareResult

Check your understanding

- You should never use a print statement in a function definition.

- Although you should not mistake print for return, you may include print statements inside your functions.

- You should not have any statements in a function after the return statement. Once the function gets to the return statement it will immediately stop executing the function.

- This is a very common mistake so be sure to watch out for it when you write your code!

- You must calculate the value of x+y+z before you return it.

- Python will automatically calculate the value x+y+z and then return it in the statement as it is written

- A function cannot return a number.

- Functions can return any legal data, including (but not limited to) numbers, strings, lists, dictionaries, etc.

What is wrong with the following function definition:

def addEm(x, y, z):

return x+y+z

print('the answer is', x+y+z)

- The value None

- We have accidentally used print where we mean return. Therefore, the function will return the value None by default. This is a VERY COMMON mistake so watch out! This mistake is also particularly difficult to find because when you run the function the output looks the same. It is not until you try to assign its value to a variable that you can notice a difference.

- The value of x+y+z

- Careful! This is a very common mistake. Here we have printed the value x+y+z but we have not returned it. To return a value we MUST use the return keyword.

- The string 'x+y+z'

- x+y+z calculates a number (assuming x+y+z are numbers) which represents the sum of the values x, y and z.

What will the following function return?

def addEm(x, y, z):

print(x+y+z)

- 25

- It squares 5 twice, and adds them together.

- 50

- The two return values are added together.

- 25 + 25

- The two results are substituted into the expression and then it is evaluated. The returned values are integers in this case, not strings.

What will the following code output?

def square(x):

y = x * x

return y

print(square(5) + square(5))

- 8

- It squares 2, yielding the value 4. But that doesn't mean the next value multiplies 2 and 4.

- 16

- It squares 2, yielding the value 4. 4 is then passed as a value to square again, yeilding 16.

- Error: can't put a function invocation inside parentheses

- This is a more complicated expression, but still valid. The expression square(2) is evaluated, and the return value 4 substitutes for square(2) in the expression.

What will the following code output?

def square(x):

y = x * x

return y

print(square(square(2)))

- 1

- cyu2 returns the value 1, but that's not what prints.

- Yes

- "Yes" is longer, but that's not what prints.

- First one was longer

- cyu2 returns the value 1, which is assigned to z.

- Second one was at least as long

- cyu2 returns the value 1, which is assigned to z.

- Error

- what do you think will cause an error.

What will the following code output?

def cyu2(s1, s2):

x = len(s1)

y = len(s2)

return x-y

z = cyu2("Yes", "no")

if z > 0:

print("First one was longer")

else:

print("Second one was at least as long")

- square

- Before executing square, it has to figure out what value to pass in, so g is executed first

- g

- g has to be executed and return a value in order to know what paramater value to provide to x.

- a number

- square and g both have to execute before the number is printed.

Which will print out first, square, g, or a number?

def square(x):

print("square")

return x*x

def g(y):

print("g")

return y + 3

print(square(g(2)))

- 3

- The function gets to a return statement after 2 lines are printed, so the third print statement will not run.

- 2

- Yes! Two printed lines, and then the function body execution reaches a return statement.

- None

- The function returns an integer value! However, this code does not print out the result of the function invocation, so you can't see it (print is for people). The only lines you see printed are the ones that occur in the print statements before the return statement.

How many lines will the following code print?

def show_me_numbers(list_of_ints):

print(10)

print("Next we'll accumulate the sum")

accum = 0

for num in list_of_ints:

accum = accum + num

return accum

print("All done with accumulation!")

show_me_numbers([4,2,3])

8. Write a function named same that takes a string as input, and simply returns that string.

9. Write a function called same_thing that returns the parameter, unchanged.

10. Write a function called subtract_three that takes an integer or any number as input, and returns that number minus three.

11. Write a function called change that takes one number as its input and returns that number, plus 7.

12. Write a function named intro that takes a string as input. This string ist intended to be a person’s name and the output is a standardized greeting. For example, given the string “Becky” as input, the function should return: “Hello, my name is Becky and I love SI 106.”

13. Write a function called s_change that takes one string as input and returns that string, concatenated with the string “ for fun.”.

14. Write a function called decision that takes a string as input, and then checks the number of characters. If it has over 17 characters, return “This is a long string”, if it is shorter or has 17 characters, return “This is a short string”.