2.6. Lists¶

The designers of Python had many choices to make when they implemented the list data structure. Each of these choices could have an impact on how fast list operations perform. To help them make the right choices they looked at the ways that people would most commonly use the list data structure, and they optimized their implementation of a list so that the most common operations were very fast. Of course they also tried to make the less common operations fast, but when a trade-off had to be made the performance of a less common operation was often sacrificed in favor of the more common operation.

Two common operations are indexing and assigning to an index position. Both of these operations take the same amount of time no matter how large the list becomes. When an operation like this is independent of the size of the list, it is \(O(1)\).

Another very common programming task is to grow a list. There are two

ways to create a longer list. You can use the append method or the

concatenation operator. The append method is \(O(1)\). However,

the concatenation operator is \(O(k)\) where \(k\) is the

size of the list that is being concatenated. This is important for you

to know because it can help you make your own programs more efficient by

choosing the right tool for the job.

Let’s look at four different ways we might generate a list of n

numbers starting with 0. First we’ll try a for loop and create the

list by concatenation, then we’ll use append rather than concatenation.

Next, we’ll try creating the list using list comprehension and finally,

and perhaps the most obvious way, using the range function wrapped by a

call to the list constructor. Listing 3 shows the code for

making our list four different ways.

Listing 3

def test1():

l = []

for i in range(1000):

l = l + [i]

def test2():

l = []

for i in range(1000):

l.append(i)

def test3():

l = [i for i in range(1000)]

def test4():

l = list(range(1000))

To capture the time it takes for each of our functions to execute we

will use Python’s timeit module. The timeit module is designed

to allow Python developers to make cross-platform timing measurements by

running functions in a consistent environment and using timing

mechanisms that are as similar as possible across operating systems.

To use timeit you create a Timer object whose parameters are two

Python statements. The first parameter is a Python statement that you

want to time; the second parameter is a statement that will run once to

set up the test. The timeit module will then time how long it takes

to execute the statement some number of times. By default timeit

will try to run the statement one million times. When it’s done it

returns the time as a floating-point value representing the total number

of seconds. However, since it executes the statement a million times, you

can read the result as the number of microseconds to execute the test

one time. You can also pass timeit a named parameter called

number that allows you to specify how many times the test statement

is executed. The following session shows how long it takes to run each

of our test functions a thousand times.

from timeit import Timer

t1 = Timer("test1()", "from __main__ import test1")

print(f"concatenation: {t1.timeit(number=1000):15.2f} milliseconds")

t2 = Timer("test2()", "from __main__ import test2")

print(f"appending: {t2.timeit(number=1000):19.2f} milliseconds")

t3 = Timer("test3()", "from __main__ import test3")

print(f"list comprehension: {t3.timeit(number=1000):10.2f} milliseconds")

t4 = Timer("test4()", "from __main__ import test4")

print(f"list range: {t4.timeit(number=1000):18.2f} milliseconds")

concatenation: 6.54 milliseconds

appending: 0.31 milliseconds

list comprehension: 0.15 milliseconds

list range: 0.07 milliseconds

In the experiment above the statement that we are timing is the function

call to test1(), test2(), and so on. The setup statement may

look very strange to you, so let’s consider it in more detail. You are

probably very familiar with the from...import statement, but this

is usually used at the beginning of a Python program file. In this case

the statement from __main__ import test1 imports the function

test1 from the __main__ namespace into the namespace that

timeit sets up for the timing experiment. The timeit module does

this because it wants to run the timing tests in an environment that is

uncluttered by any stray variables you may have created that may

interfere with your function’s performance in some unforeseen way.

From the experiment above it is clear that the append operation at 0.31

milliseconds is much faster than concatenation at 6.54 milliseconds.

We also show the times for two additional methods

for creating a list: using the list constructor with a call to range

and a list comprehension. It is interesting to note that the list

comprehension is twice as fast as a for loop with an append

operation.

One final observation about this little experiment is that all of the times that you see above include some overhead for actually calling the test function, but we can assume that the function call overhead is identical in all four cases so we still get a meaningful comparison of the operations. So it would not be accurate to say that the concatenation operation takes 6.54 milliseconds but rather the concatenation test function takes 6.54 milliseconds. As an exercise you could test the time it takes to call an empty function and subtract that from the numbers above.

Now that we have seen how performance can be measured concretely, you can

look at Table 2 to see the Big O efficiency of all the

basic list operations. After thinking carefully about

Table 2, you may be wondering about the two different times

for pop. When pop is called on the end of the list it takes

\(O(1)\), but when pop is called on the first element in the list—or anywhere in the middle it—is \(O(n)\)

The reason for this lies

in how Python chooses to implement lists. When an item is taken from the

front of the list, all the other elements in

the list are shifted one position closer to the beginning. This may seem

silly to you now, but if you look at Table 2 you will see

that this implementation also allows the index operation to be

\(O(1)\). This is a tradeoff that the Python designers thought

was a good one.

Operation |

Big O Efficiency |

|---|---|

|

O(1) |

|

O(1) |

|

O(1) |

|

O(1) |

|

O(n) |

|

O(n) |

|

O(n) |

|

O(n) |

|

O(n) |

|

O(k) |

|

O(n) |

|

O(n+k) |

|

O(n) |

|

O(k) |

|

O(n log n) |

|

O(nk) |

As a way of demonstrating this difference in performance, let’s do

another experiment using the timeit module. Our goal is to be able

to verify the performance of the pop operation on a list of a known

size when the program pops from the end of the list, and again when the

program pops from the beginning of the list. We will also want to

measure this time for lists of different sizes. What we would expect to

see is that the time required to pop from the end of the list will stay

constant even as the list grows in size, while the time to pop from the

beginning of the list will continue to increase as the list grows.

Listing 4 shows one attempt to measure the difference

between the two uses of pop. As you can see from this first example,

popping from the end takes 0.00014 milliseconds, whereas popping from the

beginning takes 2.09779 milliseconds. For a list of two million elements

this is a factor of 15,000.

There are a couple of things to notice about Listing 4. The

first is the statement from __main__ import x. Although we did not

define a function, we do want to be able to use the list object x in our

test. This approach allows us to time just the single pop statement

and get the most accurate measure of the time for that single operation.

Because the timer repeats a thousand times, it is also important to point out

that the list is decreasing in size by one each time through the loop. But

since the initial list is two million elements in size, we only reduce

the overall size by \(0.05\%\).

Listing 4

pop_zero = Timer("x.pop(0)", "from __main__ import x")

pop_end = Timer("x.pop()", "from __main__ import x")

x = list(range(2000000))

print(f"pop(0): {pop_zero.timeit(number=1000):10.5f} milliseconds")

x = list(range(2000000))

print(f"pop(): {pop_end.timeit(number=1000):11.5f} milliseconds")

pop(0): 2.09779 milliseconds

pop(): 0.00014 milliseconds

While our first test does show that pop(0) is indeed slower than

pop(), it does not validate the claim that pop(0) is

\(O(n)\) while pop() is \(O(1)\). To validate that claim

we need to look at the performance of both calls over a range of list

sizes. Listing 5 implements this test.

Listing 5

pop_zero = Timer("x.pop(0)", "from __main__ import x")

pop_end = Timer("x.pop()", "from __main__ import x")

print(f"{'n':10s}{'pop(0)':>15s}{'pop()':>15s}")

for i in range(1_000_000, 100_000_001, 1_000_000):

x = list(range(i))

pop_zero_t = pop_zero.timeit(number=1000)

x = list(range(i))

pop_end_t = pop_end.timeit(number=1000)

print(f"{i:<10d}{pop_zero_t:>15.5f}{pop_end_t:>15.5f}")

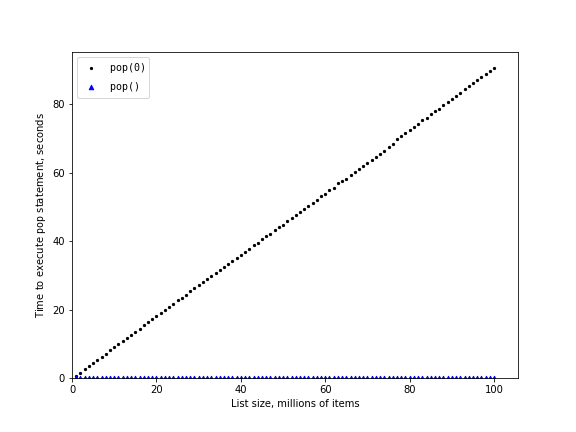

Figure 3 shows the results of our experiment. You can see

that as the list gets longer and longer the time it takes to pop(0)

also increases while the time for pop stays very flat. This is

exactly what we would expect to see for an \(O(n)\) and

\(O(1)\) algorithm.

Figure 3: Comparing the Performance of pop and pop(0)¶

Among the sources of error in our little experiment is the fact that there are other processes running on the computer as we measure that may slow down our code, so even though we try to minimize other things happening on the computer there is bound to be some variation in time. That is why the loop runs the test one thousand times in the first place to statistically gather enough information to make the measurement reliable.