1.14. Optional: Graphics in C++¶

C++ is designed with the principal that speed is more important than safety and error-checking. This differs from the majority of other programming languages, which tend to be considerably more restrictive in regards to aspects such as memory allocations and resource management. C++ is translated to “machine language” when it is compiled, which is a step skipped by other languages.

This difference is what allows C++ to be as fast as it is, which also makes it particularly good for graphically-intensive applications. Graphical applications heavily leverage memory management to display every pixel you see on your screen. Many languages do not allow for the creation of arrays like in C++, which are just “chunks” of memory of a fixed size. Furthermore, running directly on the hardware allows C++ to communicate better with other components of your computer, such as your graphics processing unit, or “GPU”. This is one of many reasons C++ is considered an industry standard for high-performance graphics applications, such as video games or software used for visual effects in movies.

Turtle graphics are a popular and simple way for introducing programming to beginners. It was part of the original Logo programming language developed by Wally Feurzeig, Seymour Papert and Cynthia Solomon in 1967.

Imagine Turtles as being a digital marker used for drawing various shapes, images, and designs. Drawing with Turtles can be as basic as a simple triangle and as complex as a highly detailed fractal image. Nearly all commands used when drawing with Turtles are as simple as telling your Turtle to move forward, backward, left, and right in as few or many steps as desired.

1.14.1. Introduction to Turtles¶

Visual representations afford students an opportunity to observe a facet of computer science from an alternative point of view: rather than waiting anxiously for the print statement to come around after your program churns, you get a visual representation of the concept itself. This is particularly useful for abstract concepts such as recursion and iteration.

For C++, a library titled C-Turtle is used to provide an equivalent of Python’s Turtles. It acts as a close replacement to provide easy to use graphics to C++, while maintaining the objects and commands present in Python. It was developed by Jesse Walker-Schadler at Berea College during the summer of 2019 and can be found on GitHub here: https://github.com/walkerje/C-Turtle/

Below is a comparison of two versions, C++ and Python, which should do the same thing. Try running both and comparing how the code looks between the two versions.

- Students receive instant feedback and gratification for their work.

- Correct!

- Students will pay less attention to how their code works, and more attention to its end result.

- Incorrect, because equal thought must be put into the usage of Turtles as well as the outcome.

- Students get more acquainted with RGB values common in web development.

- Incorrect, because RGB values are not the focus or reason behind using Turtles.

- Students will be more comfortable working with concepts they are used to, such as Turtles.

- Correct!

Q-3: How might students benefit from having a visual representation such as C-Turtle? Check all that apply.

1.14.2. Turtle & TurtleScreen¶

Turtles must exist on a TurtleScreen to be used. The TurtleScreen object must

be created before you can create a Turtle object for this reason.

ct::TurtleScreen screen;

ct::Turtle turtle(screen);

//Notice how the Screen is given to our Turtle when we create it.

Closing a TurtleScreen when you’re done with it is fairly simple to do. For this chapter,

only the method bye is used. Calling it is not completely necessary, as it is also called

automatically if it, or an equivalent method, hasn’t been called. When working outside of the

textbook, the exitonclick method is also available.

screen.bye();

Turtles are based on the following premise: “There is a turtle on a canvas with a colored pen

attached to their tail.” In this case, the canvas is a TurtleScreen. This Turtle will

follow any command you give it, which consist of telling it to go certain directions, what color

of pen to use, when to raise or lower its pen, and others. Below is an outline of commonly used

methods when working with turtles.

Method Name |

Description |

|---|---|

turtle.left |

turns the turtle a certain number of units to the left. |

turtle.right |

turns the turtle a certain number of units to the right. |

turtle.penup |

raises the paint pen on the end of the turtle’s tail. |

turtle.pendown |

lowers the paint pen on the end of the turtle’s tail. |

turtle.fillcolor |

tells the turtle what color the inside of the shape will be. |

turtle.beginfill |

tells the turtle to begin filling a shape as it moves. |

turtle.endfill |

tells the turtle to finish filling the shape it has created as it moved. |

turtle.pencolor |

tells the turtle what color it will draw with. |

turtle.width |

tells the turtle how large of a paint pen to use. |

turtle.speed |

tells the turtle how fast it should go, faster or slower than the hare. |

turtle.back |

moves the turtle back a number of units. |

turtle.forward |

moves the turtle forward a number of units. |

turtle.goto |

tells the turtle to move to a specific coordinate. |

turtle.write |

tells the turtle to write some kind of text. |

Many of these methods are used alongside one-another to create different images. All speeds are measured on a range of 1 to 10,

the latter being the fastest and the former being the slowest. The exception is the fastest speed, TS_FASTEST,

which is set to 0. The TS prefix represents “Turtle Speed”.

CTurtle Name |

Speed |

|---|---|

TS_FASTEST |

0 |

TS_FAST |

10 |

TS_NORMAL |

6 |

TS_SLOW |

3 |

TS_SLOWEST |

1 |

Consider the following annotated example.

The order of operations given to a turtle is important, as some actions must be completed

one after another. A good example of this is the begin_fill and end_fill

pattern, which must be called in that specified order to actually fill a shape.

Construct a program that fills a green triangle using begin_fill and end_fill using the example code above as a guide.

There are 14 commonly used methods for Turtles. Many of them have names that indicate what they do. See if you can match each method description with their names!

-

Q-6: :match_1: turn to the left.|||turtle.left

:match_2: turn to the left.|||turtle.right

:match_3: pick pen up.|||turtle.penup

:match_4: put pen down.|||turtle.pendown

:match_5: what color to fill drawing with.|||turtle.fillcolor

:match_6: start filling the shape.|||turtle.beginfill

:match_7: stops filling the shape.|||turtle.endfill

:match_8: change the pen color.|||turtle.pencolor

:match_9: change the pen size.|||turtle.width

:match_10: change the speed|||turtle.speed

:match_11: move backward.|||turtle.back

:match_12: move forward.|||turtle.forward

:match_13: move to a specific coordinate.|||turtle.goto

:match_14: write some text to the canvas.|||turtle.write

Match the turtle method descriptions to the methods they belong to.

1.14.3. Geometry, Shapes, and Stamps¶

Every basic shape in CTurtle is a set of coordinates. Within the CTurtle library we have the

choice of a select few shapes that we can me our Turtles inhabit.

To change the appearance of your Turtle, you can use shape to set your Turtle to

one of four default shapes, or a custom shape. CTurtle features four default shapes, triangle,

indented_triangle, square, and arrow.

The following code example shows how to set the shape of a turtle by giving it the name of a shape.

turtle.shape("square");

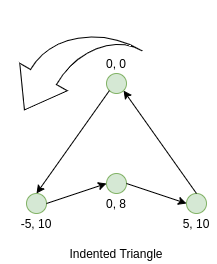

Given that all primitive shapes are defined as a collection of points, all of the default shapes are also defined this way. Polygons, for custom and default shapes, must have their points defined in counter-clockwise order to appear correctly. This is due to the mathematics behind filling arbitrary shapes, and is a limitation almost all computer graphics need to abide by. Consider the order of their points in the following table, and how they could be considered “counter-clockwise”. They are in order from top to bottom, and one edge exists between the first last points for each of these shapes. Please note that positive Y coordinates are lower on the screen, while negative Y coordinates are higher on the screen. Coordinates at the origin– that is, coordinate 0x, 0y– is at the “point” or “tip” of the turtle. This is why most of the default shapes have their first coordinate there.

triangle |

indented_triangle |

square |

arrow |

|---|---|---|---|

(0, 0) |

(0, 0) |

(-5, -5) |

(0, 0) |

(-5, 5) |

(-5, 10) |

(-5, 5) |

(-5, 5) |

(5, 5) |

(0, 8) |

(5, 5) |

(-3, 5) |

. |

(5, 10) |

(5, 10) |

(-3, 10) |

. |

. |

. |

(3, 10) |

. |

. |

. |

(3, 5) |

. |

. |

. |

(5, 5) |

Using the default indented_triangle shape as an example, Figure 1 shows the nature of the counter-clockwise order.

Figure 1: Indented Triangle Definition¶

The example code below illustrates how to create your own shape. We use the Polygon class to represent our shape.

For this example, we take the triangle default shape and make every Y coordinate negative to make it appear upside-down.

ct::Polygon upside_down_triangle = {

{0, 0}, //First point

{-5, -5}, //Second point

{5, -5} //and so on.

};

The following code is a full example for setting your turtle to a custom shape. Feel free to mess around with the coordinates of the polygon, you might surprise yourself with what shape you end up with!

Stamps provide a way to make several copies of the shape of the turtle across the screen without having to trace each

shape individually with the turtle. This can be used for a variety of visual effects, however it is often used as a

time-saving utility. Stamps can be placed with the stamp method of Turtle objects, which returns an integer

that acts as the ID of the stamp that has been placed. The clearstamp method of the Turtle object can

be used to delete a single stamp from the screen, while the clearstamps method is used to delete multiple

stamps at once.

The following code is a full example showing how to combine custom shapes with stamp placement.

1.14.4. Advanced Features¶

Turtles are a large tool, and thus have a lot of options dictating how they function.

Some features and functionality are more complicated than others, relating to the inner workings

of turtles themselves. A few of these include the tracer and undo methods, and also screen modes.

Screen modes dictate the direction of angle measurements. This means that, depending on which mode a TurtleScreen

object is in, positive angles could represent clockwise rotations or counterclockwise rotations. The mode method

for TurtleScreen allows you to set which mode a screen is in.

Mode |

Default Rotation |

Positive Angles |

|---|---|---|

SM_STANDARD |

East |

Counterclockwise |

SM_LOGO |

North |

Clockwise |

Regarding angles, Turtles can use both degrees and radians for their rotations. You can choose between the two using the

radians and degrees methods for the Turtle object. By default, all angles are measured in degrees. This option

only effects methods regarding rotation, such as left and right.

turtle.degrees();

turtle.right(90);//90-degree turn to the right

turtle.radians();

turtle.left(1.5708f);//Equivalent rotation in radians to the left.

The tracer(N) method is used to control how many times the Turtle is actually

drawn on the screen. This method belongs to the TurtleScreen object, and effects

all turtles that are on the screen. The N in the method represents the input,

only allowing the TurtleScreen to display one frame out every N.

screen.tracer(12);

//Show one out of every 12 frames of animation.

This can be combined with the speed method available to turtles to achieve very quickly

drawn images. The maximum speed a Turtle can have, TS_FASTEST, completely disables animation

for Turtles between movements and rotations. This allows the tracer setting to directly relate

to the total number of actions the turtle makes. The actions the turtle takes happen regardless

of whether or not they are actually shown on the screen.

screen.tracer(3); //Show one out of every 3 frames of animation.

turtle.speed(ct::TS_FASTEST); //Disables Turtle animation

turtle.forward(50);//This is not shown on-screen...

turtle.right(90);//Neither is this...

turtle.forward(50);//But this action is, because it is third out of three.

A frame of animation is added for almost every action a turtle takes, regardless of whether or not

the turtle is moving or adding something to the screen. This includes methods like

begin_fill and end_fill, which don’t do anything visually but do

tell the turtle to start or stop tracking its own movements.

Consider the following example and related questions.

#include <CTurtle.hpp>

namespace ct = cturtle;

int main(){

ct::TurtleScreen screen;

ct::Turtle turtle(screen);

turtle.speed(ct::TS_FASTEST);

screen.tracer(6);

for(int i = 0; i < 3; i++){

turtle.right(60);

turtle.forward(50);

}

screen.bye();

return 0;

}

- 3

- Incorrect! Consider how many actions the turtle takes in the for loop.

- 6

- Incorrect! Consider the tracer setting for the screen.

- 1

- Correct!

- 12

- Incorrect! Consider how many actions the turtle takes in the for loop.

Q-9: How many frames of animation does the above code create?

Similarly to tracer settings, every action a turtle takes is also added to the undo queue. This allows it to keep track

of actions it is performing over a period of time. The queue is only allowed to grow to a certain size, starting at 100 actions total.

This is modifiable through the setundobuffer method that belongs to turtles. Every action is added, even if

the action doesn’t change anything visually. This feature is comparable to the “undo” tool available in most text editors.

Turtles can “undo” their progress with the undo method.

- 3

- Incorrect! Consider how many actions the turtle takes in the for loop.

- 6

- Correct!

- 1

- Incorrect! Consider how many actions the turtle takes in the for loop.

- 12

- Incorrect! Consider how many actions the turtle takes in the for loop.

Q-10: How many actions will be in the turtle’s undo queue for the code above?