5.2. Jupyter Notebooks¶

The files you will be working with are called Jupyter Notebooks. This comes from the idea of a lab notebook, where you combine figures, data that you have gathered, and explanations about how the data fits the theory. In our case, a notebook can be used to write and run programs and to edit accompanying text. This makes it convenient as a way to deliver some of this course content, but you can also use it to create a report that contains coding (and its output including graphs).

5.2.1. Text Cells¶

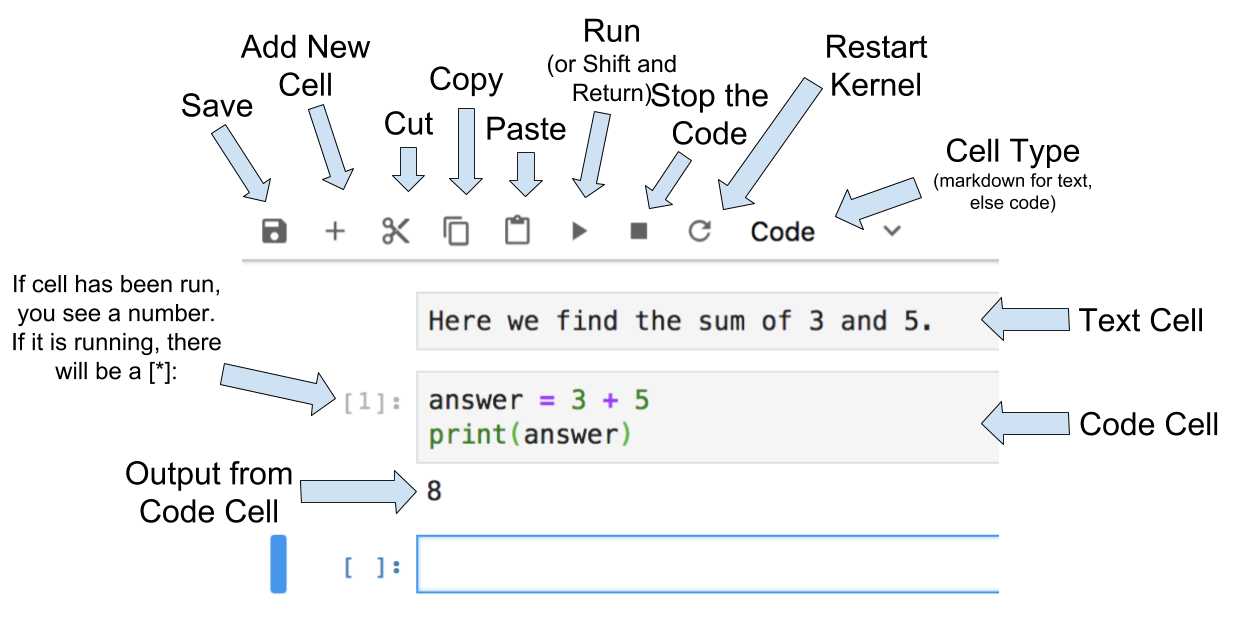

In a notebook, each rectangle containing text or code is called a cell.

Text cells (like the one shown in Figure 1) can be edited by double-clicking on them. They’re written in a format called Markdown. You don’t need to learn Markdown, but you might pick up some aspects of the language from looking at the content that we provide.

After you edit a text cell, click the “run cell” button at the top that looks

like ▶ or hold down shift + return to confirm any changes.

Practice editing a text cell by making any part of the text in the cell that you choose bold. Bold is created in Markdown by surrounding the word or phrase you want bolded with double underscores or double asterisks.

You can also double-click on any text cell that is given to you to see how the authors of the notebook created various bits of styling like italics or inline images like this one that explains the various parts of Jupyter.

Figure 1: Anatomy of JupyterLab Notebook¶

5.2.2. Code Cells¶

Alternatively, cells can contain Python 3 code. Clicking “run cell” for a code cell will execute the content of the cell and print out the output of the code snippet right below the code cell. Try running this cell.

3+5*4%43

23

This doesn’t work just for arithmetic operations but any Python code that you might write.

import math

circle_areas = []

for i in range(1, 5):

circle_areas.append(math.pi * i**2)

circle_areas

[3.141592653589793, 12.566370614359172, 28.274333882308138, 50.26548245743669]

Notice that if a cell ends with a value by itself on a line, the resulting value gets printed in the output. This doesn’t work if the cell ends with an assignment of a value to a variable.

a = 5

Note that no output is produced when you run the previous cell. However, the

value of a is saved and is available in other cells.

a * a

25

25

This is useful because it means that we can put import statements and the

time-consuming reading of large data sources in one cell (usually) at the start

of the notebook, and experiment with manipulations of that data in later cells

without having the wait to reload the data. The caveat to this is that each cell

is executed when you run it, so you could accidentally or willfully run cells

out of order. Below is an example.

# Run this cell once

my_list = ["red", "green", "blue"]

# Run this cell twice

my_list.append("purple")

# Run this cell once

print(my_list)

['red', 'green', 'blue', 'purple']

Notice that my_list contains “purple” twice even the code above only adds it

once. In general, you should write your code assuming that each cell is run once

from top to bottom. There’s even a menu to help you do that. The “Run” menu has

“Run All Above Selected Cell” and “Run All Cells” functions that allow you to

get your notebook in a predictable state if you ever get confused by having run

cells multiple times or out of order.